2006 10 15

From: nytimes.com

In January of 1929, the creator of Time magazine lay dying in a Brooklyn hospital bed. He was thirty years old. Briton Hadden did not look like a man with only a few weeks to live. His family had decided not to tell him of his dire condition. But the doctors believed he stood almost no chance. Hadden, who had only just begun the creative revolution that would transform journalism in the subsequent century, had drunk and partied his way to his deathbed.

In January of 1929, the creator of Time magazine lay dying in a Brooklyn hospital bed. He was thirty years old. Briton Hadden did not look like a man with only a few weeks to live. His family had decided not to tell him of his dire condition. But the doctors believed he stood almost no chance. Hadden, who had only just begun the creative revolution that would transform journalism in the subsequent century, had drunk and partied his way to his deathbed.

In the giddy and rebellious decade just ending, a time when youth shattered old rules of behavior, a time that saw the emergence of jazz, modern literature, and transcontinental flight, Hadden had influenced popular culture in ways that would permeate the American mindset, changing the way people thought and acted in the twentieth century. By the age of twenty-five, he had created the first magazine to make sense of the news for a broad national audience. By the age of twenty-seven, he had invented a writing style that brought great events to life, informing a wide group of Americans. By the age of thirty, he had made his first million dollars.

"Anyone over thirty is ready for the grave," Hadden had proclaimed during the heady years of his quick rise to influence. A muscular man with a barrel chest and a square jaw, he looked more like an athlete than an editor. But there were signs of eccentric genius in his intense face: the gray-green eyes that twinkled when he laughed, the pencil-thin mustache that drew attention to a mischievous smile. He had lived fast all the way, dancing to "Hindustan" at the Plaza, hosting outrageous cocktail hours that mixed ministers with call girls, shocking friends by showing up for parties in an asbestos suit and stamping out cigarettes on the arm of his jacket.

In a hurry to achieve all he had dreamed, Hadden had rushed about with his coat collar up, chewing gum, chain-smoking, and swinging his cane. When he talked, he often barked. When he liked a joke, his raucous laugh shot through the room as if fired from a machine gun. Writers called him "The Terrible-Tempered Mr. Bang" because he growled and stamped his feet when they used a word he didn't like, but it was all part of his act-a beautiful insane act that swept people up within his orbit and filled them with the magic of his grand persona. People loved Hadden; they admired him. The dramatist Thornton Wilder called him "a prince."

Now almost thirty-one, Hadden was wasting away of an unknown ailment. Doctors had diagnosed him with an infection of streptococcus, and they guessed that the bacteria had spread through his bloodstream to reach his heart. Hadden, a lover of animals, believed he had contracted the illness by scooping up a wandering tomcat and taking it home to feed it a bowl of milk, only to be attacked and scratched. Now Hadden was losing strength. Without penicillin, his doctors were all but helpless, and they were beginning to consider desperate measures-a direct infusion of the antiseptic Mercurochrome, perhaps, or a massive series of blood transfusions.

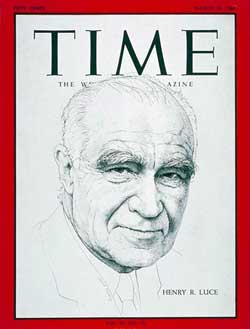

In this dark hour, the most frequent visitor to Hadden's bedside, aside from his devoted mother, was a tall, thin man with slightly hooded eyes framed by a pair of thick, bushy eyebrows, a receding line of straw-colored hair, and an open, angelic face. Equally as attractive as Hadden, he also looked his diametric opposite. Hadden's business partner, Henry R. Luce, was penetrating where Hadden was witty, analytical where Hadden was creative, organized and careful where Hadden was spontaneous and reckless. They had been drawn together as only opposites can be almost since the moment they had met. Their rivalry was legend, and so was their friendship.

In this dark hour, the most frequent visitor to Hadden's bedside, aside from his devoted mother, was a tall, thin man with slightly hooded eyes framed by a pair of thick, bushy eyebrows, a receding line of straw-colored hair, and an open, angelic face. Equally as attractive as Hadden, he also looked his diametric opposite. Hadden's business partner, Henry R. Luce, was penetrating where Hadden was witty, analytical where Hadden was creative, organized and careful where Hadden was spontaneous and reckless. They had been drawn together as only opposites can be almost since the moment they had met. Their rivalry was legend, and so was their friendship.

Conjoined by mutual brilliance, a passion for the news, and the love for a good fight, they had competed ardently and at times bitterly for fifteen years. They had drawn intellectual sustenance from each other. At Yale, in the secret society of Skull and Bones, their fellow club mates had drawn a picture of them on horseback, dueling with lances, because each was the greater warrior for facing the other. During the Great War, at a dusty training camp in South Carolina, they had brainstormed the idea that would shape their lives and those of millions more. Believing people nationwide were outrageously ignorant, they resolved to create a magazine that would make sense of the news for the average American. A few years later, they quit their jobs to launch Time, the first newsmagazine. Publishers predicted failure, but within a few years the awkward upstart was growing faster than all of its competitors.

Hadden and Luce launched their magazine in a time when a young nation stood open to the influence of adventurers and iconoclasts, people with new ideas of how the world should be run and the courage, ambition, and drive to make their dreams reality. It was Hadden, Time's creative genius and editor, who would shape the style in which Americans think about and tell the news. In doing so, he set the foundation for the newspaper and magazine chains, radio and television networks, cable stations and Internet sites that have come to occupy a prominent place in the national culture.

Hadden told the news just as he viewed it-as a grand and comic epic spectacle. He hooked readers on the news and sold them on its importance by flavoring the facts with color and detail, and by painting vivid portraits of the people who made headlines. Hadden's entertaining writing style proved so popular that it quickly spawned imitators. As the rest of the media took up Hadden's style of narrative reporting, journalists transformed themselves from mere recorders into storytellers. The burgeoning national news media acquired a grip on the American imagination and a power unprecedented in public life.

That achievement alone would qualify Hadden as one of the few seminal publishers in American history. But that was not all Hadden did. Within a year of printing the first issue of Time, he created the first radio quiz show. Three years after that, he began publishing a trade magazine about advertising that took business reporting in a new direction. In the last year of his life, he dreamed up the idea for a magazine devoted exclusively to sports, which later became Sports Illustrated. Sniffling with the first hints of illness, he talked excitedly of his idea for a new picture magazine, which he hoped to call Life. Hadden's ideas were so influential that a single page from one notebook found among his things after his death would serve as a virtual road map for the next half-century of the company he founded.

Luce called Hadden an "original" and was deeply influenced by his ideas. Throughout their many battles, whether for the editorship of the school paper or for creative control of Time, it was Hadden who won. Luce, who couldn't stand to lose, had been forced to content himself with second place for more than a decade. He had worked as Hadden's deputy in both prep school and college. During the founding of Time Incorporated, Hadden had acted more "on the originality side," as one friend put it, while Luce had served as the creative "brake." Luce had continued to live in Hadden's shadow ever since. For years, when Luce walked in the door of the New York Yale Club, the waiters would greet him as "Mr. Hadden," because Luce ate there on Hadden's account.

But Luce was a dogged competitor, capable of acquiring new talents, and each time they raced Luce finished a hair closer. In recent years, Luce had pressed Hadden for control of the company. Offended by Luce's desire for power, Hadden had been further depressed by a string of romantic failures. In his final few years, he had turned to the bottle, driven drunk through town, picked fights in speakeasies, and spent nights in jail. Finally it seemed that the brighter of two brilliant candles was about to flicker out. "It's like a race," Hadden had once said of their strange friendship. "No matter how hard I run, Luce is always there." Now Luce was at Hadden's deathbed, ready to slog out the final grueling lap of their rivalry.

For several months Luce had been developing a plan to publish the company's second major product-a business magazine to be called Fortune. Hadden was opposed. Believing the business world to be vapid and morally bankrupt, he had devoted the last few years to lampooning businessmen in print, even when they happened to be Time's own advertisers. Luce was adamant. He kept coming to Hadden's bedside, discussing draft articles and mock-ups. Hadden, true to form, had been drawn into a series of lengthy arguments. Day after day, Hadden and Luce had yelled at each other-so loudly that Hadden's nurse could hear them from behind the closed door.

From the perspective of Luce and others at the company, Hadden was out of his head. "He's a sick man," Hadden's cousin told Luce. An executive later reflected, "He was too sick to know and comprehend." Luce was going ahead without Hadden; it wasn't necessary to fill him in on every detail. But there Luce was at Hadden's bedside, insistently pressing his case. Luce would stay for an entire hour, and when he finally got up to leave Hadden would be visibly exhausted. The doctors, believing Hadden was wasting his precious energies, came to fear the moment of Luce's arrival. But Luce continued to visit, and Hadden's condition continued to deteriorate.

As Hadden lay near death, too weak to speak above a whisper, he and Luce had their decisive conversation. No one else would ever know what transpired that January day in that Brooklyn hospital room. It was only known that Luce came by and sat behind a closed door. But the story that later circulated among Time's employees was that Luce brought up the major financial matter that lay between Time's young founders. Together, Hadden and Luce held slightly more than half of the voting stock in Time Incorporated-just enough, together, to maintain control. Singly, however, each of them owned less than 30 percent of the voting stock. If Hadden died, Luce could lose control of the company-unless somehow he got his hands on Hadden's stock.

In that moment it was nearly certain that Hadden would die, and that he would die holding the shares his successor desperately needed to keep control of Time. Given his ambitions, Luce would have been foolish not to ask for those shares. One rumor passed along by Luce's detractors was that he broached the question as Hadden lay dying-an awkward matter that would have abruptly shocked Hadden with the full gravity of his rapidly deteriorating condition. Luce, of course, told a different story. He claimed he did not ask Hadden for his shares; in fact, there was never any "open recognition" between them that Hadden was dying. But if this were the case, it would be difficult to explain what happened next.

A few days later, Hadden took a decisive step. He asked his roommate, a young lawyer named William J. Carr, to draw up a will. Carr, who didn't have much experience with estates, took out a piece of paper and simply wrote, "I, Briton Hadden, declare this to be my last will and testament." He must have strained to hear his friend, who was speaking so quietly by then that he could hardly express his desires at all. Clinging to life but fast approaching death, Hadden forbade his family from selling his stock in Time Inc. for forty-nine years. When Carr handed Hadden the will, he felt too weak to sign his name, but he managed to guide his hand to the line. There Hadden scrawled an "X." In settling his estate, Hadden prevented Luce from gaining immediate control of the company they had founded together.

Hadden's heart gave out one month later-six years, almost to the hour, since he had sent the first copy of Time to press. It was four A.M. in New York, three A.M. in Chicago, where the latest issue rolled off the press, too soon to mention Hadden's passing. The next week, a short notice led off Time's National Affairs section: "Creation of his genius and heir to his qualities, Time attempts neither biography nor eulogy of Briton Hadden. But there will be privately printed, within the year, a book about him which will be sent to all who ask."

That book was not printed for more than twenty years. Within a week, Luce removed Hadden's name from the masthead of the magazine. Hadden's name would not return until after Luce's death nearly forty years later. Within a year, Luce violated Hadden's death wish by negotiating a deal with his bereaved family to purchase Hadden's shares in Time Inc. at a bargain-basement price. Freed from Hadden's shadow, Luce quickly grew into his talents, becoming the most influential magazine publisher in history and for decades the most powerful media mogul in America. Employing his editor's post as a lectern, Luce became the missionary of the media, an imperialist who consistently urged Americans to spread democracy and capitalism throughout the globe.

As he traveled the world, delivering hundreds of speeches about everything from his childhood in China to his years at Yale, Luce repeatedly claimed credit for Hadden's ideas. In all of his talks before a public audience, Luce mentioned Hadden's name only a handful of times. If asked to discuss Hadden, Luce would downplay his partner's role, saying Hadden died just as Time was "beginning to see the light." When a friend who deeply missed Hadden gently brought him up in conversation, Luce sniffed, "Time was his monument, and he done it." By the time Luce died in 1967, Hadden was nothing but a faint memory.

Now, nearly eighty years after his untimely death, Hadden is all but erased from history. One recent book described him as a "footnote" in the faded past of the company he brought to life. Luce's face has been printed on a postage stamp and his achievements have been chronicled in multiple biographies, while Hadden has been the subject of a single book, commissioned by Luce. Long out of print, it was derided by the writer's own brother as an "affront to the memory of Briton." Considering the magnitude of Hadden's achievements, it seems natural to ask why he has all but vanished from the historical record.

For more than half a century, the answer to this question has been kept under lock and key in the archives of the company Hadden and Luce founded together. Recently I was permitted to view these records. Suddenly a world long hidden from view lay bare, revealing the extraordinary story of a tortured friendship that ignited a media revolution. The following narrative describes how two young men transformed the way we make sense of the world around us. It is the story of perfect opposites who formed an epic partnership, of a rivalry so ferocious as to create the best of friends. It begins with their birth, on opposite sides of the world, at the dawn of the twentieth century. . . .

Excerpted from The Man Time Forgot by Isaiah Wilner Copyright © 2006 by Isaiah Wilner. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Article from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/08/books/chapters/

1008-1st-wiln.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&ref=books

Comment on this article

Related: Time Magazine Co-founder Briton Hadden

Yale's Skull & Bones Society Members